How Our Union Is Fighting Pay Inequity

One of the top issues our members want to address collectively as a union is pay inequity. We know vast disparities in pay exist at The Times, which we’ve heard about both through our organizing conversations and through an important salary sharing effort we began during our organizing drive.

We’ve heard from tech workers in other workplaces who are interested in organizing that resources on our salary sharing project would be valuable. Here’s a guide to starting your own salary sharing process and an invitation to join us in the best way to fight for pay equity: unionizing your workplace.

It’s easy to feel overwhelmed and powerless when you’re not sure whether you’re being paid fairly. Sharing salary data with each other, and having conversations around that data, can build solidarity as you form a union. You can start regardless of how established your campaign is. Here’s how our union gathered information to inform our conversations on pay equity.

I. We Knew Our Rights

In the US, we have the federal right to discuss pay and working conditions with coworkers under the National Labor Relations Act (NLRA).

Salary sharing is a protected activity. An employer in the US may not retaliate in any way when employees share details about compensation or talk about working conditions with each other.

That said, and we’ll return to the point: you should run the survey outside of work hours and house data off of company equipment, products, and platforms.

If your employer reaches out to ask you about salary sharing, you don’t have to answer questions about it! State that you know your right to discuss compensation with coworkers. Still, your employer might try to intimidate you. Whoever is the public host of the sheet should be comfortable reinforcing your rights if your boss tries to pressure you. Make collective decisions on salary sharing wherever you can.

II. We Started Slow

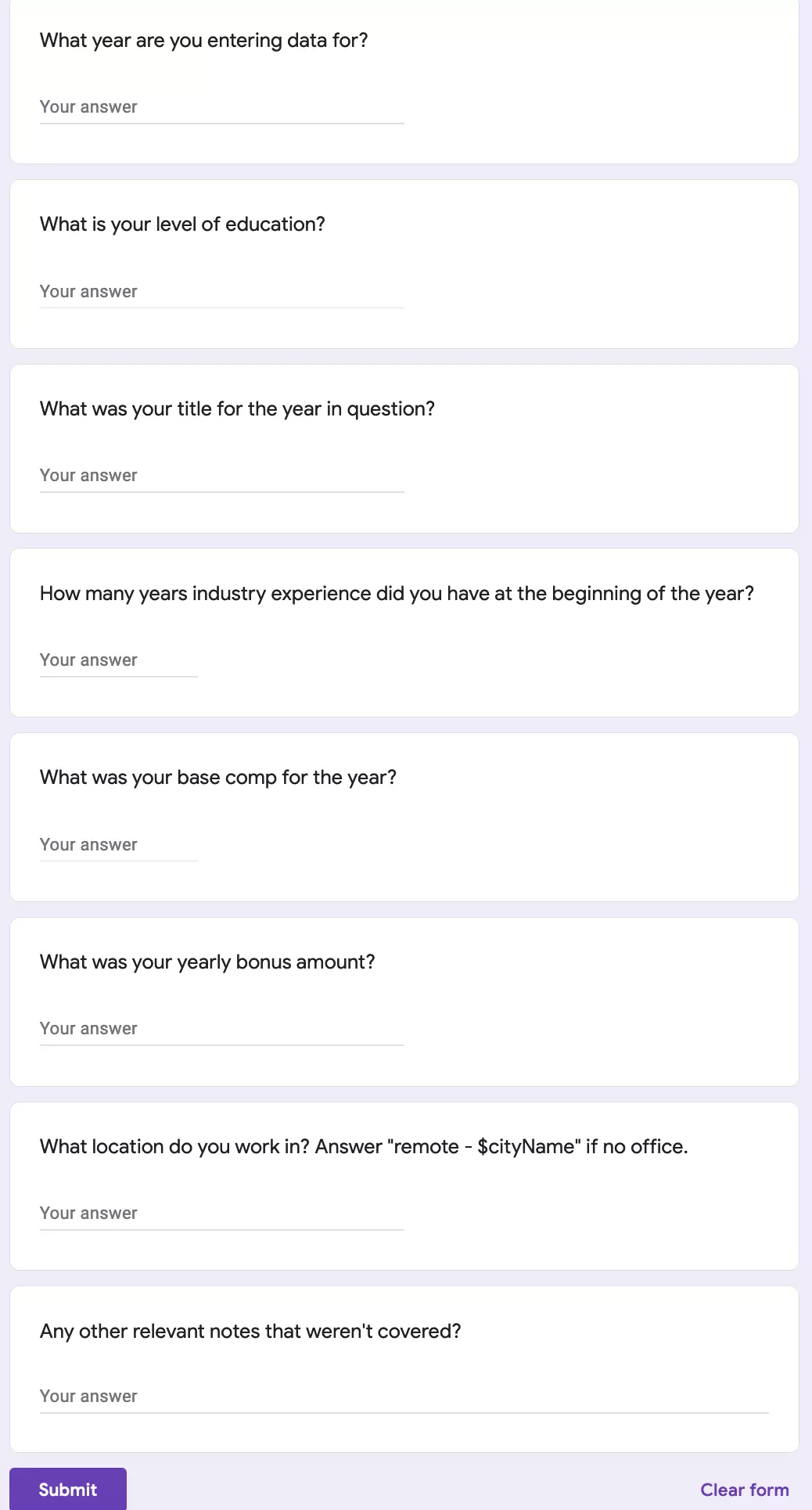

Before we solicited salary data from non-supervisory coworkers, we gathered a few salaries from people we knew and trusted. We were clear about our process and intentions. We discussed why it helps everyone to talk about compensation. We collected anonymous salary data by sharing a Google Form where each respondent could enter information on their pay.

When we shared the form, we said that we intended to share anonymous salary data in a spreadsheet accessible to our co-workers. We described how having a few data points to seed the spreadsheet would give everyone better confidence and anonymity with subsequent submissions. One tip: share your salary first, proactively, when asking coworkers about theirs.

III. We Hosted a Spreadsheet, and We Welcomed Everyone in Our Union Community to View and Contribute

Once we had a few data points, it was time to make the data available for our union community. We hosted our spreadsheet in a public channel inside a Slack space that we created for our union–one that we accessed only via personal accounts and devices. We invited co-workers only via one-on-one conversations and union meetings off of company premises. Pinned to the top of the channel were the form to add salary data and the spreadsheet to view all the salary data that had been added so far.

If you host your data in a location where you might receive fake submissions from people who are not your coworkers, you can optionally password protect the document with a word or phrase only an employee would be able to find out.

One point to emphasize: make anonymized salary data freely available to everyone in your union space, including people who have not yet shared their salaries.

Our salary sharing gained momentum over time. The more salaries were in the sheet, the more people felt empowered to add their own. We made all fields optional to encourage people to share only what they were comfortable sharing.

IV. We Talked About Pay

This was the fun part: the actual conversations that happened in our salary sharing channel and organizing conversations. The data in the spreadsheet was anonymous, but, leading by example, we encouraged each other to use the channel to share salary journeys: non-anonymous posts of pay history, with as much narrative detail as each person wanted to bring.

Employers benefit by keeping us in the dark about each other’s pay. This culture can make people afraid to share pay with others. If it turns out we make more than our coworkers—what if they resent us? It’s hard to overstate how much our experience showed the contrary. The atmosphere in our salary sharing conversations was one of mutual appreciation, compassion, and common purpose. That owes largely to context: we started salary sharing in a union community, one formed on the premise that we want what is best for each other.

There was real hurt when people found out–as many did–that they were being underpaid. But the blame fell rightly to the employer, not fellow colleagues. And people in the channel were glad to hear about the highest salaries in each job level. Sharing them was a clear way for more privileged workers to support their marginalized colleagues, because the highest salaries in each job level showed the rest of us what it was possible to ask for. Thanks to data in the channel, members of our community asked for and were given raises that they would have never known to seek.

The channel was also our space for broader conversations on how to negotiate, industry trends, and pay equity. It helped us establish a new culture around pay. The chance to partake in salary sharing became a great motivation for people to join our union space, where they got involved in conversations on all the other ways that we can make our workplace better together, like advocating for job protections, career development opportunities, more affordable healthcare, and stronger diversity, equity, and inclusion policies.

V. We Formed a Union

Salary sharing is a great way to build the community, trust, and solidarity it takes to build a strong union. Access to salary data puts an employee in a more equal position when negotiating with their employer: non-union workers usually only know their own salary, whereas bosses know all worker salaries. Knowing more can give you more confidence in a negotiation.

Without a union, there are inherent limitations. An employer will always have more accurate, complete data than we can gather from anonymous, voluntary sharing. More significant: when we’re forced to negotiate pay as individuals, our leverage is limited.

By forming a union, we win the right to bargain collectively for an employment contract to establish equitable pay and higher pay minimums. And, as soon as our union is certified, we win the right to make Requests for Information: inquiries on data pertaining to working conditions in our unit–including comprehensive salary data–that the company is legally required to disclose. Having the full data set allows us to comprehensively identify pay inequities and set benchmarks for a strong contract.

Helpful Resources

Cher Scarlett started an open source pay transparency survey which is free to reference and use on Github, shared here with permission. Cher also gave advice on many parts of this post throughout. Thank you Cher!: https://github.com/cherscarlett/pay-transparency-survey

https://www.levels.fyi/ can be a good source of tech pay data

Here’s a public salary spreadsheet filled out by women in tech: 2021 Female Salaries in Tech

Ask a Manager has a crowdsourced salary spreadsheet: Ask A Manager Salary Survey 2019 (Responses)

Read about how salary spreadsheets at Google helped uncover pay inequities: https://www.nytimes.com/2017/09/08/technology/google-salaries-gender-disparity.html

Do you want to get started unionizing your workplace? We want to help! Contact us at nyttech@nyguild.org, DM us @NYTGuildTech on Twitter, or reach out to our friends at CODE-CWA to learn about joining the labor movement in the tech industry.